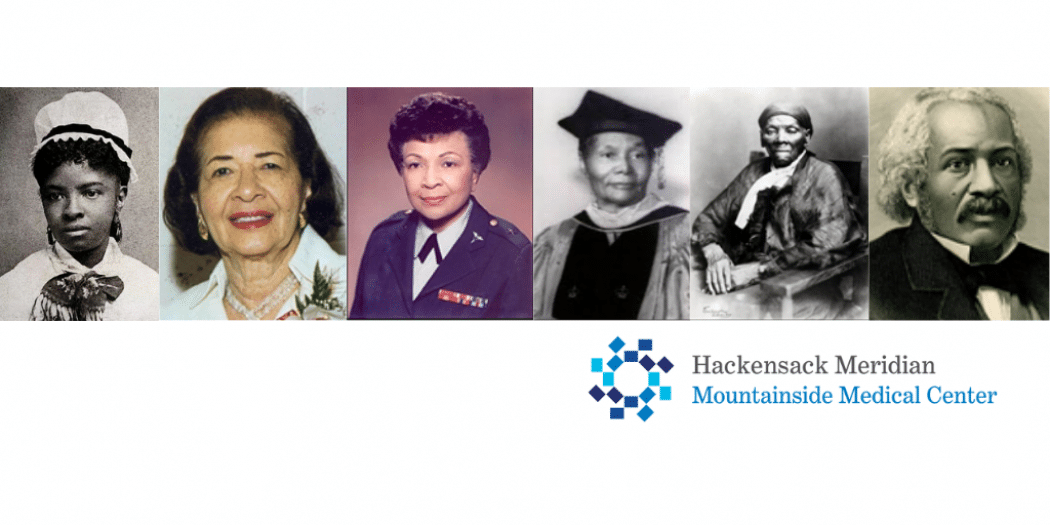

This Black History Month, as we reflect on the incredible nurses who have led us through a global pandemic, we’re pausing to spotlight six nurses throughout history whose tremendous accomplishments have paved the way for the nurses of today.

Mary Eliza Mahoney

Born in 1845, Mary Eliza Mahoney envisioned greater opportunities for African American women and saw nursing as a way of getting there. She began working at the New England Hospital for Women and Children as a teen and was later admitted to the hospital’s professional graduate school for nursing. While the demands of the coursework were daunting, Mahoney became one of the first women to finish the program in 1879. With this accomplishment, she also became the first African American in the United States to receive a professional nursing license.

Betty Smith Williams

Betty Smith Williams was born to a minority rights activist and member of the South Bend, Indiana Chapter of the NAACP. She was raised to advocate for equality and did just that. In 1954, she became the first African American student to graduate from the nursing school at Case Western Reserve University. Williams continued making history as the first black person to teach at the college or university level in the state of California.

In 1972, in a continued effort to bolster opportunities for African American women in the nursing profession, she co-founded the National Black Nurses Association (NBNA) in Cleveland, Ohio.

Hazel W. Johnson-Brown

Hazel Johnson-Brown was born in 1927 in West Chester, Pennsylvania. She was raised in a household that valued discipline, integrity and the pursuit of education. Despite many barriers to entry, she lived out those ideals.

When she came of age to pursue a career, she applied to the Chester School of Nursing, where she was denied admission based on being African American. Still determined, Johnson-Brown continued applying and was accepted to the Harlem Hospital School of Nursing in New York, where she graduated in 1950.

Later, she returned to Pennsylvania and got involved in the Philadelphia Veterans Administration (VA) Hospital and quickly moved up the ranks, becoming a head nurse after three months. She was intrigued by all that the Army had to offer and enlisted as a nurse in 1955. She held several roles in the military, ultimately becoming the first black woman to be promoted to brigadier general.

After an exceptional career in the U.S. Army and medical field, Johnson-Brown died of Alzheimer’s disease in 2011.

Lillian Holland Harvey

Lillian Holland Harvey was a firm believer in continued education. After earning a nursing degree, master’s degree and a doctorate, Harvey was offered the role of director of nurse training at the Tuskegee School for Nurses in 1945. Just three years later, she was promoted to the dean of the school. One of her first initiatives as dean was to transform the three-year nursing program into a baccalaureate program, which elevated the reputation of the school.

Harvey was elected into membership in the Alabama Healthcare Hall of Fame in 1999.

Harriet Tubman

Best known for her work freeing slaves on the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman also worked as a nurse with the Union Army. Tubman had an innate way of caring for others and figuring out what exactly was wrong. Many of the remedies came from watching her mother, as she would boil different roots and herbs into medicinal concoctions. Although Tubman never received payment for her time as a nurse during the Civil War, she saved a countless number of soldiers with her incredible knowledge of homeopathic treatments.

Tubman is a pivotal figure in our country’s history and while rattling off her long list of accomplishments, her nursing career often gets overlooked, we remember her as a trailblazer for nurses everywhere.

James Derham

Despite never receiving an M.D., James Derham was the first African American man to practice medicine in the United States. Born into slavery, he piqued an interest in the profession by assisting his owners who were physicians. He began working as a nurse at the urging of one of his owners and in 1790, it’s believed Derham was able to escape slavery by purchasing his freedom.

Derham opened his own practice where he specialized in throat diseases and explored the relationship between climate and certain diseases. He had an extremely popular practice until 1801 when regulations were passed that barred Derham and others from practicing medicine without a formal degree. It’s unknown what happened to Derham after 1802, but his legacy will never be forgotten.